Table of Contents

Introduction

This article addresses the third question in the “100 Questions in Islamic History” series, examining the reliability of Islamic historical records. The discussion explores how Islamic historiography developed its distinct scientific methodology through three key elements: religious preservation, freedom from governmental influence, and the implementation of the chain of narration (isnad) system. The complete series is available for further exploration.

The Uniqueness of Islamic History: Where Faith Meets Civilization

Question 3: What makes Islamic history reliable, given that historical accounts often contain myths and exaggerations? How can Muslims trust these historical records?

Answer: This critical question connects to concerns about historical accuracy, particularly when contemporary events face distortion.

Islamic civilization stands unique because religion shaped its core foundation. In Michael Hart‘s book “The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History“, he selected Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon Him) as history’s most influential figure. When asked why he, as a Christian, ranked Muhammad (Peace be upon Him) above Jesus, Hart explained:

“He was the only man in history who was supremely successful on both the religious and secular levels. Of humble origins, Muhammad founded and promulgated one of the world’s great religions, and became an immensely effective political leader“

Throughout history, other influential figures typically succeeded in either the religious or political sphere, but not both simultaneously. Moses passed away in the wilderness before establishing a state, while Jesus – according to Christian accounts (though Islamic belief holds that ALLAH raised him) – faced crucifixion, indicating political defeat. Historical figures like Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Darius built civilizations without establishing religions.

This distinction highlights a crucial point: Islamic historical documentation emerged primarily to preserve religious teachings rather than glorify rulers, states, or civilizations.

The Unique Foundation of Islamic Historical Documentation

Consider the historical work of Khalifah bin Khayyat, who passed away in 240 AH. He stated:

“Through history, people know the timing of their pilgrimage and prayers, the completion of their women’s waiting periods, and the due dates of their debts“

His focus centered on documenting history to help people understand their religious obligations and social responsibilities.

Unlike contemporary historical narratives that often serve political agendas through media manipulation, Islamic historiography developed independently of ruler influence. This independence preserved historical authenticity.

Al-Tabari, who died in 310 AH, shared similar views with Khalifah ibn Khayyat. Later, Al-Sakhawi, from the ninth century AH, expanded on history’s purpose:

“Among the benefits of history is knowing the dates of imams and narrators, their births and deaths“

He included practical matters like waiting periods and debt payments, while emphasizing the importance of documenting scholarly lineages and significant events.

This methodical documentation helped Muslims understand religious evolution, particularly regarding divine revelation. For instance, consider these Quranic verses about intoxicants:

- “O you who have believed, do not approach prayer while you are intoxicated until you know what you are saying…“1 (Suraat ‘An-Nissaa’, 4:43)

- “O you who have believed, indeed, intoxicants, gambling, [sacrificing on] stone altars [to other than ALLAH], and divining arrows are but defilement from the work of Satan, so avoid it…“2 (Suraat ‘Al-Maa’idah, 5:90)

Islamic historians researched the chronological order of these verses to understand the gradual implementation of religious laws. If the first verse preceded the second, it showed a gradual prohibition of alcohol. If reversed, it indicated an initial complete prohibition followed by prayer-specific guidance.

Islamic History: Religious Preservation Over Political Power

Islamic history emerged as a religious science dedicated to understanding divine guidance and prophetic teachings, rather than serving political authorities. This fundamental characteristic distinguishes it from politically-motivated historical documentation. Islamic historiography developed as part of religious scholarship, not political science, with its origins rooted in preserving and understanding religious teachings rather than commissioned by rulers.

This point addresses contemporary concerns about historical manipulation. When individuals witness events firsthand – such as during the Egyptian or Syrian revolutions – and then see these events misrepresented in media, with perpetrators rewarded and victims falsely labeled, it raises doubts about historical authenticity.

However, early Muslim historians developed their methodology independently of political influence. Their primary motivation was religious understanding, leading them to create an unprecedented system called “Isnad” (chain of transmission). This scientific approach to historical documentation set Islamic historiography apart from other civilizations’ historical records.

The Chain of Narration: Islam’s Scientific Method for Historical Authentication

When someone quotes a saying of Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon Him), they must provide evidence of how this knowledge reached them. The chain typically follows this pattern: “So-and-so told me, who heard from so-and-so, who heard from Abu Hurayra, who heard the Prophet say”. This system initiates a thorough examination of each narrator’s character: their religious commitment, integrity, potential for bribery, and possible motives for narrating specific traditions.

After verifying individual narrators through detailed biographical records, scholars examine the connections between them. This involves confirming whether narrators actually met each other, which requires precise knowledge of their birth and death dates. The entire chain undergoes scrutiny for any breaks or complications – a specialized aspect of chain transmission science.

Even after establishing a sound chain, scholars analyze the content itself. They check if stronger, more reliable chains contradict this narration. If contradictions exist, the weaker narration becomes classified as irregular (shaadh). Sometimes, despite having both sound chain and content, scholars might still reject a hadith due to subtle defects that defy general classification.

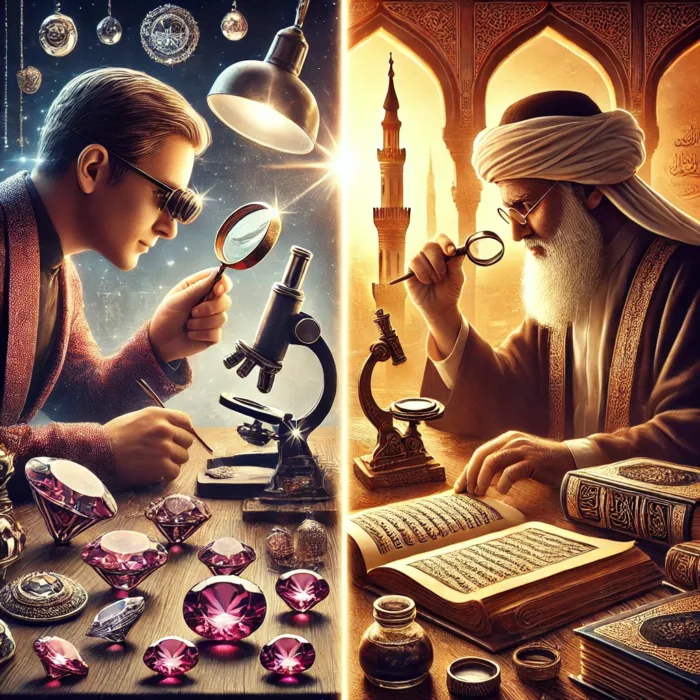

This meticulous approach resembles an experienced jeweler who can identify counterfeit gold or fake diamonds through expertise rather than following set rules. Each case presents unique characteristics requiring careful examination.

Islamic historiography grew from this precise methodology of religious scholarship. This explains why Al-Tabari’s historical works consistently include chains of narration – without them, his work would have lacked credibility in the scholarly environment of his time, where chain-verified transmission represented the accepted standard of documentation.

The Academic Rigor: Parallels Between Modern Peer Review and Islamic Historical Verification

In today’s academic world, research gains credibility through peer review – when multiple specialists evaluate its adherence to scientific principles. This modern practice parallels the historical chain of transmission system in Islamic scholarship. During early Islamic times, no statement gained acceptance without citing its complete chain of sources, creating a rigorous system of verification.

Consequently, there’s a difference between peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed studies. This situation in the past was called narrating with a chain of transmission. There was no such thing as saying something from your own mind; every narrative had to cite who told you, from whom, from whom, from whom… to the end of that narrative.

This scholarly environment demanded more than just source citation. It required narrators to demonstrate religious commitment, trustworthiness, precision, and expertise. Since this system developed to preserve religious knowledge rather than serve individual interests, it maintained independence and objectivity.

The scientific atmosphere in early Islamic scholarship produced unique methodologies that set Islamic historical documentation apart from other civilizations. These included:

- The science of narrator classifications

- The science of chain transmission

- The science of authentication and invalidation

These methodological innovations led scholars like Imam Ibn Hazm to note that Islam stands unique among religions in having verifiable historical documentation. He observed that while other religious texts and historical figures – from Moses to Buddha – lack scientific means of verification due to breaks in transmission chains and undocumented periods, Islamic sources maintained continuous, verified chains of transmission.

Scientific Authenticity in Islamic History: Human Factors and Methodological Safeguards

The existence of scientific methodologies in Islamic historical documentation does not guarantee absolute accuracy in every narration. Rather, it provides tools for examination and verification. The Islamic scholarly environment developed systems like chain transmission to enable critical evaluation, but unverified narrations remain subject to scrutiny, comparing them with authenticated sources or maintaining cautious skepticism.

Human imperfection means various issues could arise in historical narration:

- Deliberate fabrication by dishonest narrators

- Exaggeration in storytelling

- Honest mistakes due to poor memory or confusion

Islamic heritage acknowledges these possibilities while providing methodological tools for verification. This system developed to preserve religious authenticity rather than defend individuals or interests.

This commitment to methodological integrity appears clearly in hadith scholarship. Scholars classified certain narrations about prominent Islamic figures – like Aisha, Khadija, Fatima, Abu Bakr, and Umar (May ALLAH be pleased with Them) – as weak, despite their elevated status. The methodology focused purely on verifying whether Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon Him) actually spoke these words, regardless of the content’s merit.

This scientific rigor led to precise distinctions in authenticity. Hadith scholars often note: “This is a weak hadith but its meaning is correct” – indicating that while the specific narration lacks strong authentication, its message aligns with established Quranic verses or verified hadiths.

Islamic Historical Archives: The Twin Pillars of Collection and Verification

Islamic historical documentation benefited from a dual approach, as exemplified by Al-Tabari’s methodology. In his introduction, he clearly stated: “My book serves as an archive, not everything in it is correct, and I don’t accept everything in it“. He further explained: “Whatever readers find objectionable or listeners deny in this book, let it be known that these are merely transmissions as they reached us“.

This approach provided two significant advantages:

- Comprehensive collection of historical accounts

- Establishment of frameworks for examination

This can be compared to creating an archive of various news sources about contemporary events, such as the Al-Aqsa flood, containing reports from Egyptian, Zionist, Jordanian, and Syrian newspapers, including statements from different commentators. Such an archive preserves information while enabling critical evaluation.

Future generations might struggle to distinguish between different sources and their reliability, just as someone centuries later might not recognize the differences between various contemporary figures. In such cases, they would need to refer to the evaluations of hadith scholars who systematically documented the reliability of narrators, classifying them as “trustworthy and established” or “unreliable and dishonest”.

Islamic Scholarship: The Legacy of Independent Historical Documentation

Islamic historical documentation combines thoroughness in collection with analytical capability. Al-Tabari’s historical work, written over eleven centuries ago, continues to inspire scholarly analysis, such as:

- “Authentic Al-Tabari’s History” and “Weak Al-Tabari’s History” by Dr. Muhammad bin Tahir Al-Barzanji

- “Abu Mikhnaf’s Narrations in Al-Tabari’s History” by Dr. Yahya bin Ibrahim Al-Yahya

- “Sayf ibn Umar’s Narrations During the Period of Civil Strife in Al-Tabari’s History” by Dr. Khalid Al-Ghaith

This ongoing analysis remains possible because of the chain of transmission system. Without it, like histories of other nations, evaluating authenticity would be impossible after such time.

However, this field requires specialist knowledge, similar to medicine, pharmacy, or engineering. The average reader of Al-Tabari’s or Ibn Al-Athir’s histories may need to consult experts to understand the authenticity of narratives or historical events, such as the period of civil strife among the companions.

Islamic historiography stands unique in its methodological approach, acknowledged by researchers and orientalists alike. A crucial distinguishing factor was its independence from political authority. Unlike other civilizations where scientific institutions operated under state control, Islamic scholarship developed independently. The Islamic state lacked modern equivalents of education ministries, cultural institutions, or state media outlets. This independence preserved scholarly integrity, as religion, not state power, shaped the civilization’s intellectual development.

Court Historians in Islamic Civilization: Unexpected Independence from Political Power

Islamic historical writing largely developed independently, exemplified by scholars like Al-Tabari who wrote without royal commission. While some sultans did commission historical works, these cases were documented and recognized.

A notable example is Abu Ishaq Al-Sabi, commissioned by the Buyid ruler to document their dynasty’s history. His candid admission – “Lies I’m fabricating and falsehoods I’m embellishing” – reveals his awareness of the political influence on his work. Yet, as Margoliouth observed, even court historians in Islamic civilization maintained surprising independence compared to their counterparts in other civilizations.

This independence stands in stark contrast to contemporary situations, such as in Egypt, where historical documentation faces two extremes:

- Writing history according to state preferences, dominating mainstream media

- Writing alternative perspectives from exile or prison

The arrest of someone merely raising a Palestinian flag illustrates current restrictions on expression. However, even Muslim historians working within royal courts maintained remarkable objectivity in their historical accounts, demonstrating a level of independence that surprised Western scholars like Margoliouth. This academic integrity distinguished Islamic historiography from other civilizations’ historical records, where court historians typically produced more politically influenced accounts.

Islamic Historiography: The Moral Foundation of Scholar-Historians

Summary response to the third question: Islamic historical documentation developed unique characteristics that safeguarded against historical distortion. This reliability stemmed from several key factors:

The foundation of Islamic historical documentation aimed to preserve religious knowledge rather than serve political interests. Most prominent historians were primarily religious scholars who maintained high moral and academic standards. Al-Tabari, for instance, achieved distinction not only as a historian but also as a Quranic interpreter with his own school of jurisprudence. His scholarly reputation depended on maintaining truthfulness and integrity.

Much like today, when a religious scholar loses credibility, their religious verdicts lose authority. Major Islamic historians like Al-Tabari, Ibn Kathir, and Al-Dhahabi were primarily Quran interpreters, reciters, and jurists who also documented history.

Islamic historiography emerged as a branch of religious sciences, maintaining relative independence from political authority. While some influence was inevitable due to human nature, the field developed systematic methodologies for examining historical narratives, particularly concerning early Islamic history.

For Muslims, the eras of Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon Him) and the Rightly-Guided Caliphs represent both historical and religious significance. Understanding their words and actions guides religious practice, making these accounts more than mere historical records. These figures serve as role models, which motivated scholars to rigorously verify all reports about them with exceptional care and precision.

The Decline of Historical Documentation: Past Excellence vs Modern Challenges

Islamic historiography holds unparalleled reliability among historical traditions, a fact acknowledged by scholars in the field. This trustworthiness stems from the unique environment in which early Muslim historians operated.

Scholars like Al-Tabari, Al-Dhahabi, and Ibn Kathir worked within an intellectual atmosphere saturated with religious knowledge, piety, and rigorous academic standards. This environment differed fundamentally from modern academic settings in its moral foundation and commitment to precision.

The contrast with contemporary historical documentation is stark. Modern academia faces multiple challenges:

- University appointments influenced by favoritism

- Academic corruption

- Purchased dissertations

- State control over historical narratives

- Limited academic independence due to financial dependence

These contemporary circumstances make it difficult to maintain the same level of historical authenticity achieved by early Muslim historians. The modern historian’s dependence on institutional employment and political constraints creates a markedly different environment from the independent scholarly tradition of Islamic historiography.

Sources:

- Mohamed Elhamy. هل تاريخنا مزور ؟ 100 سؤال في التاريخ | الحلقة 01. YouTube Video.